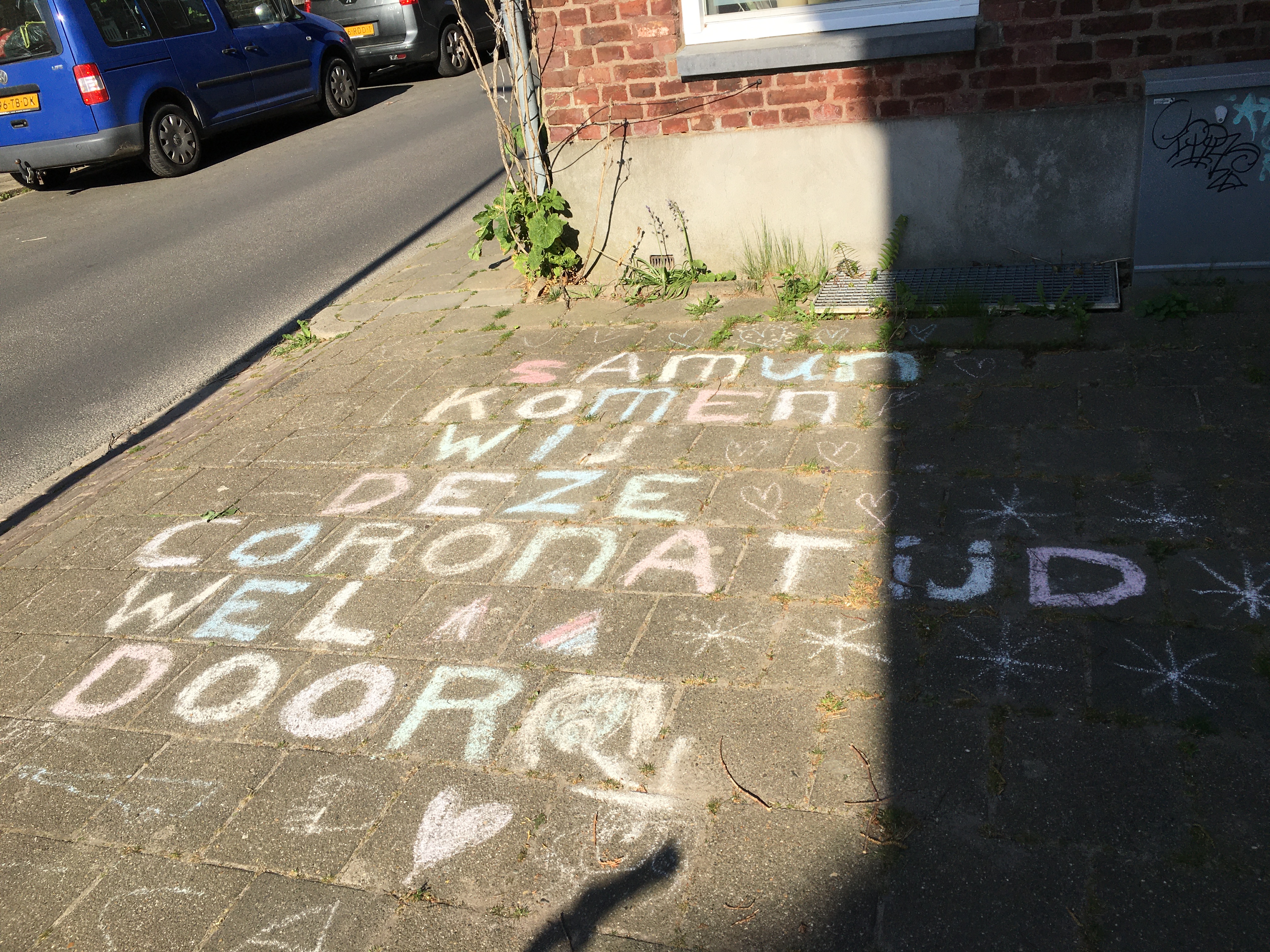

The Dutch have a way of speaking that I am always striving to emulate. This post is most importantly about how Dutch adults talk to children (feel free to skip directly to that part) and how much I love it. But first, some notes on my Dutch language-learning journey.

When you are an adult foreign language learner, you are always a pretender. You make a ridiculous number of mistakes with high frequency, and on your best days, you sound like a child (something that adulthood tries to stamp out of us, generally speaking: to be adult is to attempt to be flawless, even when we know that’s a myth – and it is certainly to avoid the shame and self-judgment inherent in frequent, frankly dumb mistakes).

DuoLingo just told me that I have been studying Dutch on and off for 5 years, since April of 2017 when we first decided we were moving to Arnhem. The journey has been mixed in methods: DuoLingo and an online class when we were in the US; informal conversation with another school parent who volunteered to teach me; tips and hints from neighbors and friends; lots of children’s book reading with Orri; and finally, an excellent teacher for the last 1.5 years who has helped me achieve leaps and bounds. I love the language (“why?” Dutch people sometimes ask me, genuinely bewildered), but progress is also the child of necessity: Although it’s possible to exist socially here almost entirely in English, there is a tremendous amount that you miss — and that you risk — when you cannot read between the lines of a tax or visa letter, or get the gist of a parent meeting at school, or read a street sign. A few days ago I had written an email to Orri’s teacher, and the note I got back seemed to me, between Google Translate and my own interpretation, a bit harsh. I can mostly read the words now — but the tone is next level, and only comes from repeat exposure. (A Dutch friend agreed to read the teacher’s note for me and assured me that, no, this is a completely straightforward business communication, it’s even friendly.)

With each level that I unlock — doing longer stretches in Dutch at the market or store, reading aloud in Dutch to Orri’s class, having full conversations with 5-year-olds who have patience for lots of errors — my jump in self confidence and pride is palpable. And, ever Lisa-Simpson-esque, I am almost silly in my eagerness to help other expat Dutch learners: Michael finally offered gently that it hurts his feelings when I correct every single Dutch sentence he ever produces.

Iver, on the other hand, makes fun of my Dutch. Like the 12-year-old boy that he is, he will press any available advantage, and although his Dutch isn’t better than mine, he rolls his eyes at my singsong voice and non-native accent, over-correcting every perceived infraction. He is old enough to have internalized the message that mistakes are bad, and so although his comprehension is pretty strong and he has several hours of Dutch in school per week, plays on a (non-American) football team in Dutch, etc., he rarely tries to speak — opting instead to mock my attempts. But I persevere, attempting to model for him that the stakes are way higher for living here and not speaking, the rewards for error-ful Dutch way greater than not even trying at all.

And Orri? He is a dream to have as a language-learning teacher, bringing all the patient tolerance of an almost 6-year-old. He loves having one area of life in which he is and always will be superior to the rest of us. At this point, he has lived in NL for 4 of his almost 6 years, and spends more hours per week in Dutch than in English (school, aftercare, football, swim lessons). He is linguistically and culturally a Dutch person who comes from an American family — whereas Iver is an American expat kid. Adults are surprised to find out that Orri is a native English speaker, when they haven’t yet met his family. He is a local, not even just Dutch but a Limburger, from this specific region with this specific accent, even though he doesn’t speak the local dialect (but claims to understand it). Though he sometimes gets tired of translating for me (“if you want to learn this word, you should look it up in the dictionary!”), he is mostly willing to listen to me work through pronunciation and answer my questions and help me with turns of phrase.

All right, enough of the personal journey. So what is Dutch and what are Dutch speakers actually like? Please allow me some stereotypes. (The Dutch weirdly love to be stereotyped and even roasted, as evidenced by their great passion for this book, which treats Dutch culture with antipathy and is incredibly insulting, in my opinion. Dutch people think it’s hilarious.)

Linguistically, Dutch has an even harsher back-of-the-throat “g” sound than German and a rolled “r,” but it’s delivered with such a sonorousness that it sometimes sounds to me like a Romance language (it is not; it’s Germanic, with the same grammar as German but tons of English and French vocabulary crossover). When my dear friend from college who now lives in Germany visited for the Netherlands for the first time, she said that Dutch sounded to her like German with a Texas twang — big wide roomy extended vowel sounds, punctuated with very precisely delivered consonants. This, to me, is a lovely analogue with Dutch culture: I have often thought that the Dutch have the structured orderliness of the Germans (which deeply pleases my German heart) with the joie de vivre of the French. They eat dinner at 6pm, put their children to bed at 8 — rust, regelmaat, en reinheid (rest, routine, and cleanliness) being the values — but love their good cheeses, their garden parties, their cozy warm spaces, their long relaxed vacations.

But the application of Dutch that I love the most, that I positively revere, is the way that Dutch people speak to children. It is perhaps more about culture than language per se, and yet as I have learned more Dutch, I’ve come to recognize it more and more. There is a specific style, an approach, that most Dutch adults take when they talk to children, and it is marvelous. First of all, they slow way, way down. They speak directly to the child they are addressing, as if no one else existed in the world. Their tone becomes caring, bright, patient, and above all, genuine. Nowhere in their speech is there a “you should have” or a “someday you’ll learn that.” It is as if in each of these conversations, the adult has taken it on themselves to do the important work of interpreting the world for the child — with zero pedantry or didacticism, and with no agenda. The sole goal seems to be to offer some perspective as if they were speaking with a peer…except slower, more thoughtful, more intentional. There is a sort of, “oh, come over here, sit next to me, there is something interesting, this is how it works, and here’s what you can expect” tone to it. No preamble — “now I will give you a lesson in x or y.” It doesn’t drone on. There is an expectation that children will pay attention, talk back, ask questions. And it is frankly incredible how well kids respond to this. Even when the adult is trying to stop a behavior or redirect a child, you would never suspect that that’s what’s happening.

Last week Michael and I took Orri with us to the optometrist. Both of us adults were trying on glasses, and the shop was relatively busy. Orri went to the rack of expensive sunglasses, and, not understanding that they were locked onto the rack, began yanking hard to try to get them off so he could try them. I started to call a “wait, stop!” correction across the store, but the sales clerk who was helping us — a young woman — walked calmly over to him, knelt down, and began to explain with zero correction exactly how the glasses were locked on, and then got her keys to show him how the lock mechanism works. She ignored us, the buyers, and all the other people in the shop, to take the time in that bright, calm, “I’m going to share this with you” voice to walk him through it. No drama, no lecture, just an opportunity to show him something.

Later, in his young-child-obsessed-with-gold mode, Orri decided that he’d like to buy one of those cheap golden glasses chains. He stood at the counter, painstakingly counting out 10 euros worth of his coins, trying to add up the amount and getting a little lost midway and just generally taking a lot of time to pay. I felt highly conscious of other people in the store, even of the fact that we needed to pay for our glasses and get home, but resisted the urge to hurry him. The sales clerk stood at the counter with him, helping him count, and then took an extended time explaining and showing him how the chain works, how the money goes in the register, how the chain goes in a little sack. And he, of course, responded, warming to her attention like a flower to the sun, expecting to be treated like a whole person, expecting to be given as much time as he needs, very much wanting to understand how things work.

This is what I mean when I say that he is Dutch: like other Dutch kids, maybe even moreso, he expects to be given the time of day, to be welcomed everywhere he goes, to be talked to and invited to engage by that bright, calm, “I’ve got this, we’ve got this together, you and I” kind of voice. He gets it at school, at swim, at football, at aftercare. It is not that Dutch adults are never tired or cross. But the default mode is warm, kind, extended engagement, not correction. No teasing, no jokes that go over his head, no dog-whistling of one’s adult authority to other adults in the room. The other adults might as well not be there. There is just the adult and the child, moving together at child speed.

I could write another 2,000 words on how I feel about this: how it often makes me tear up with gratitude, this deep level of engagement with my children, this profound patience. How I feel guilty and hopelessly flawed as a parent by comparison, rushing my children through their days and imposing an adult pace on them and often seeking to correct or curb them instead of stopping to meet them exactly where they are. (And in my own defense, I will say that I am an extremely patient parent who already strives to slow down the world as much as I can for them. But I pale in comparison to this Dutch superpower.)

Observing this adult Dutch style has influenced my parenting tremendously. And yet. There is a way in which I feel like an imposter, like this is something I can now recognize and marvel at, but which I will never get quite right. It feels like a skill handed down from generation to generation, which, somewhat like learning a language later in life, one can never achieve to a native-like level if you yourself are not native. While I believe in a growth mindset, unless you live full-time with Dutch people or are primed young with this way of being, you can only approach as a pretender. My own first family was very kind, my parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles generally patient and loving towards us kids. But I experienced most adults around me (not just family, but also teachers, shopkeepers, pastors) as stressed, with too much on their plates, no safety net, juggling to hold the pieces together, moving fast and ever faster, hurrying us through life, trying to pack the lessons in, to crack down on bad behavior. This aspect of life is now on hyperdrive in modern American interactions with kids — we adults can’t see it, it’s the air we breathe. We have naturalized things moving fast, kids needing to keep up with our pace, needing to have full lives. We can’t take on more than what’s already on our over-full plates, so we don’t stop to help random children understand things, generally speaking. We correct them and try to bend them to the world we’re/they’re in. And while this is obviously a gross stereotype, too, it’s not a criticism. Stressed adults mean stressed children. It’s not American adults’ jobs as individual people to break from the entire culture and share something that we ourselves weren’t necessarily taught how to do. It’s nigh impossible. The best we could do, which is a lot to ask most days, is to pretend.

And so I watch these Dutch adult/child interactions, and I try to get that calm, bright, sincere, patient voice in my head. I observe the speed, the intentionality of those interactions. I try to catch myself when my urge is to correct, and channel that urge into a slow, direct, warm style of engagement. I try to scrub the “hurry up” and the “stop” and the “should” from even my undertones, and approach those moments like there is something interesting to share. And sometimes, not always, but sometimes, it really works.

Here’s my second time ferrying our full-size Christmas tree home by bike.

Here’s my second time ferrying our full-size Christmas tree home by bike.