I’ve been trying to write in this blog for months. Post after post, the sentiments seem true and not true, the analysis on pointe and yet not incisive enough. Subjects that a year ago I might’ve been able to treat in my standardly-word-weighty way at 1,000 or 2,000 words, now I can no longer pin down without meandering trails into complex histories, competing theories, caveats and counter examples.

Why? It’s not that the task of writing qua writing has changed, or that I as a writer have (d)evolved so profoundly. Instead it seems that I’m marking some unspoken stage of the expat trajectory, a developmental moment in immigrant psychology. The formula goes something like:

significant geographic change + cultural and linguistic disruption + enough time

=

settling + the formation of a more persistent migrant self + more nuanced understanding

It’s not that I no longer see the differences between American and Dutch culture. It’s that my experience of those differences is ever less black-and-white, more technicolor, less romanticized. It’s getting harder to explain the differences without drawing out complexities in ways that, when I reflect back on what I’ve written, seem overburdened, TMI, either downright boring or hopelessly high-horsey. (Like, “as you can see from my treatise on the ‘managed chaos’ model of the Dutch healthcare system, capitalistic models of medical care can be effectively regulated, but individual perspective must also make a concomitant shift away from radical exceptionalism to non-consumer-based expectations about care,” blah blah blah blah blah. I’ve tried to keep it from getting that bad, but…nevertheless.)

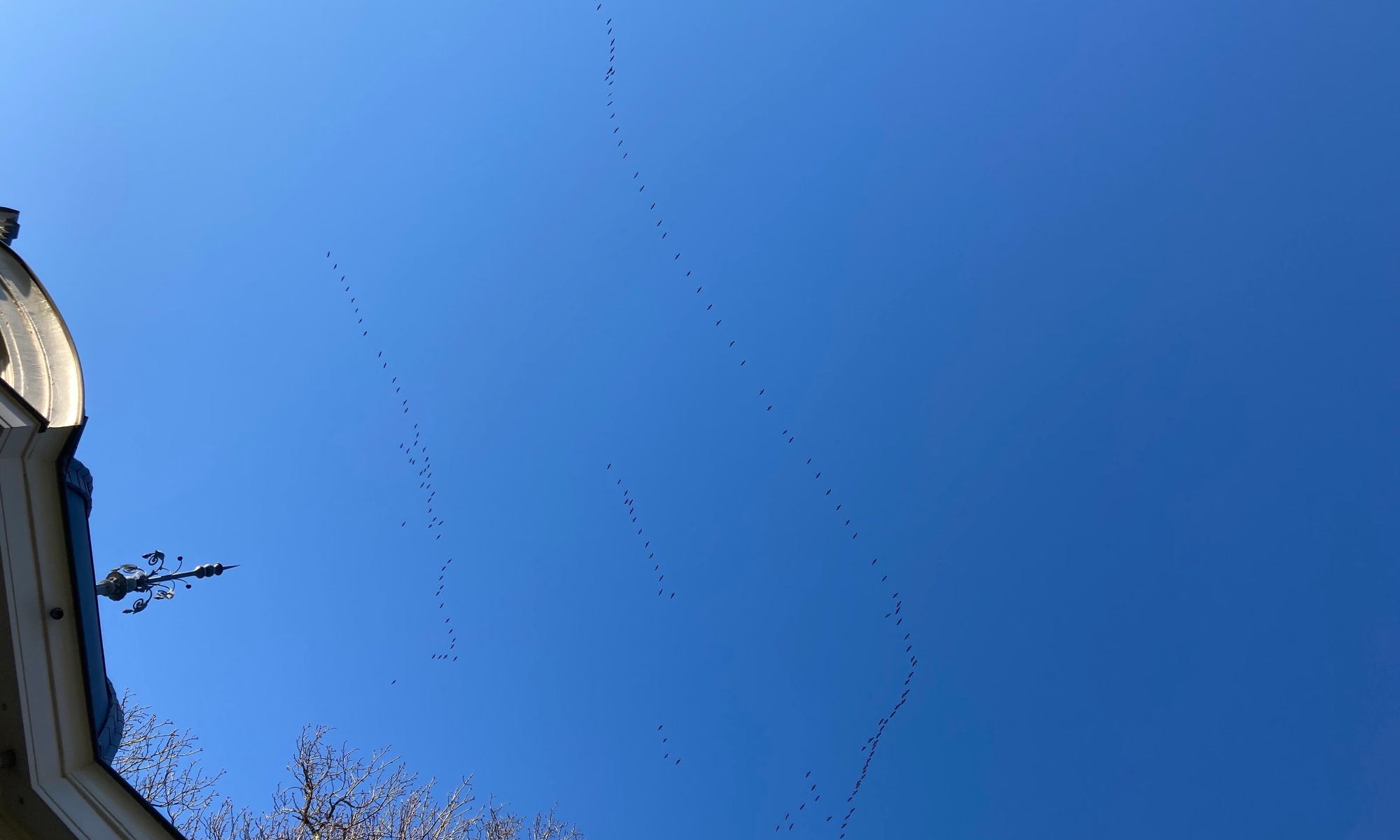

Reaching this moment in my developmental journey as an immigrant is what I wanted. I wanted the level of integration that would allow me to set aside the rose-colored glasses and apply a clearer lens to this adopted country. I wanted the same for my relationship with America — to see my homeland more gently, perhaps, but also more clearly, without the polarizing love and hate that constantly attracted and repelled. Perhaps the next important step would be to move somewhere outside of western culture, to truly shake ourselves loose, but that is not on our horizon for now. For now, this is our horizon:

Both the pandemic and the American racial reckoning have accelerated our clearer-eyed view. We will never be Dutch, but we have now lived through the Dutch version of the pandemic crucible (at least, the first year of it). Importantly, we have not lived through the American version. We have had 2 short stints of lockdown, worn masks (as adults) only in limited indoor contexts, mostly retained our freedom of movement and activity, and now will likely not have access to a Covid vaccine for months.

We have also largely missed the American racial reckoning of 2020. No matter how closely you pay attention, there is no way to live it from afar, no chance to go back and relive it later. Both fires (pandemic and reckoning) have forged American culture in ways we didn’t experience first-hand. This is true even though I am still, to borrow a phrase from my friend Jones, “commuting my soul” to America, given my work with US-based nonprofits.

I mentioned recently to an American friend the real fear that we are already so different that to return to America now would be like trying to fit back into the wild outfits you used to wear in your 20s (back before 2 pregnancies and 2 extra decades of gravity). “Of course you could still reintegrate. It hasn’t been too long!” she sweetly, cheerily pronounced. Technically we have only been away 19 months, or really 2.5 years if you count the 2017-2018 year we spent in northeast Holland. However, given all that 2020 wrought, in Human Years, it feels like we’ve been away for half a decade or more. Reintegration seems like a strange, inexplicable, almost inconceivable thing to contemplate.

Here’s an example. (Trigger warning, Americans: It involves masks). We haven’t seen most of our extended family for almost 2 years. We are eager to get back to the US for a visit but are awaiting vaccine progress on both sides of the Atlantic. For now, my strong sense is that perhaps we shouldn’t visit until masks are no longer necessary, because I cannot imagine putting a mask on my 4-year-old for an hour, much less for an entire plane ride or extended family visits.

Why not? This must sound crazy to my US people. I’m not aware of any American children that don’t wear a mask in daycare or school all day. Further, in my US social circles, masks have become so synonymous with “caring about other people” and non-masking with “every person for themselves” ideologies that I’ve seen people’s eyes widen in horror when I express that we’re not pro-masks for kids. (To be clear, if the government or school told us that kids need to mask, we would absolutely toe that line.)

But this is how we’ve been living: My younger son has never been in a mask. Only this month has the 11-year-old been required to wear a mask in the hallways at school — never in the classroom or outdoors, just when moving around the school buildings. Teachers have just begun to wear them. As with America, masks are controversial and divisive here too, especially adult masking behavior. When the primary school required parents to start wearing masks on the playground at drop-off and pick-up, our parents’ Whatsapp group imploded due to some parents refusing to mask and others insisting on it (we’re with the latter).

But the prevailing cultural value in NL has been that masks are bad for young children. They prevent kids from having normal social interactions with peers and teachers, from perceiving facial expressions, from having the freedom of childhood that is a dominant Dutch value. That, coupled with the deep-seated Dutch attitude that with most illnesses, it’s better to get sick and build natural immunity than to protect your immune system (especially for children), leads to an attitude that masks might be okay for adults, but they do more harm than good to kids.

This may seem like an irresponsible position. We Americans are, I’ve come to see, incredibly quick to moralize and to police each other’s morality (on both the right and the left). We can sometimes be unwilling to consider certain uncomfortable truths: like the idea that even science gets refracted through the prism of culture, or that to achieve true social welfare benefits like universal healthcare or public preschool, we might have to give up some personal freedoms like the right to homeschool or to choose whether to vaccinate our children.

When you live in a giant country like the US with a mainstream language and culture that gets exported to so much of the world, it can be incredibly hard to see the tradeoffs and the shades of gray. In many places in America, you don’t regularly encounter immigrants, travelers, outsiders, people outside your social class, the borderlands of other places just outside your door. And when your media (of any political persuasion) constantly reinforces the story of America as if it is the story of the whole world, it can be really difficult to get a clear view out of the nest down to the sweeping expanse of world below.

And so this is what feels increasingly hard to describe, and increasingly impossible to imagine reintegrating into. We are changing, and we cannot unsee what we have seen. We haven’t gotten a sweeping view of the whole world, but a deep, extended experience of other landscapes (NL, but also Germany and Belgium, which are both a stone’s throw away). The longer we stay, the more these landscapes comes into focus, and the more that returning to the nest seems inconceivable.

As our Canadian neighbors who’ve been here 15 years assure us, one does eventually grow accustomed to the marvelous crumbling castles and the charming half-timbered houses in sweeping river valleys and the gothic gargoyles and twisting church spires. As with anything exotic, it eventually becomes mundane. Things morph from a revelation, a permanent vacation, to just the way things are. Then does the home you’ve left behind become the exotic thing, or does one just accumulate exoticisms that all eventually resolve into normalities?

In the developmental trajectory of our lives as immigrants, this I am curious to find out.